Stretching Exercises

Stretching exercises are important, but there is some talk about whether or not stretching exercises is important for your body function. With regards to athletics and chronic pain, it’s easy to forget a little thing that happens to be the foundation of healthy muscles: stretching.

I’m not exaggerating when I say that without stretching, you are more likely to suffer from

tight muscles and have lower performance for activities.

Have you ever wondered:

“What is the benefit to stretching exercises?”

“What are the best stretching exercises?”

“Can stretching help to prevent injuries?”

“Is implementing daily stretches a good idea?”

“Does stretching improve athletic performance or does it have a negative effect?”

There is an abundance of questions around the topic of stretching, and in this guide, we

hope to answer all your questions, as well as busting any myths about stretching you may have heard of.

Benefits to Stretching Exercises

Stretching and flexibility are two topics that have been long debated in regards to finding out what works best in terms of seeing improvements without a decrease in athletic performance.

Flexibility is defined as the range of motion (ROM) possible specific to each joint or groups of joints and depends on a number of variables, including but not limited to the tightness of specific ligaments and tendons. (Nieman, 2011)

Stretching exercises are effective in increasing flexibility, reducing muscle and joint pain, improving posture, and keeping your muscles working well for whatever daily activity and/or sport you do.

Muscles have two types of receptors!

Muscles spindles and Golgi tendon organs; they monitor muscle length and tension, respectively.

Both activated by muscle stretch, however, they convey different messages.

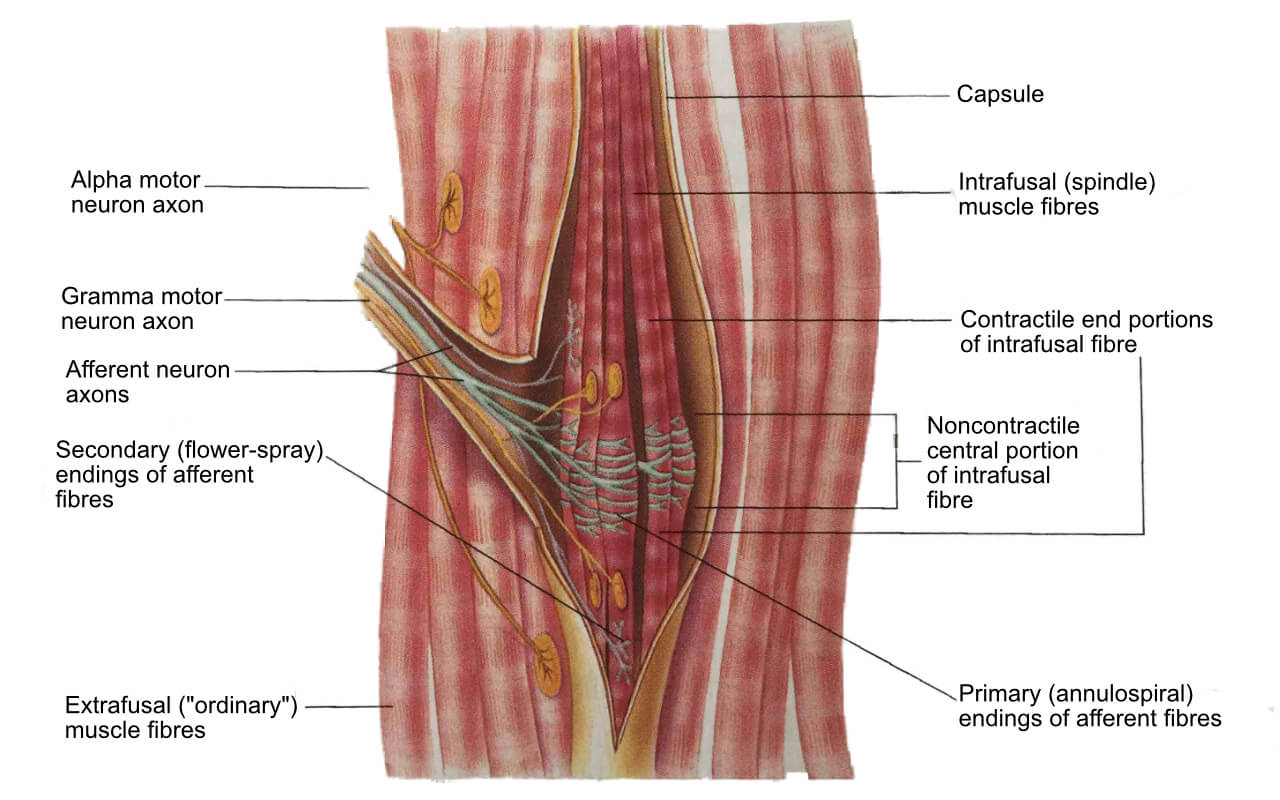

Muscle spindles are receptors that monitor changes in muscle length.

- Activated by muscle stretch

Muscles spindles are distributed throughout the fleshy part of a skeletal muscle.

- Consists of a collection of specialized intrafusal fibres that lie within a connective tissue capsule parallel to the ordinary extrafusal skeletal muscle fibres.

Intrafusal fibres

Innervated by gamma motor neurons.

- Has a non-contractible central portion, with contractible elements at the ends.

- Two types of afferent (carries info to the central nervous system) sensory endings.

- Primary (annulospiral) endings wrap around the central portion of the intrafusal fibers. They will detect changes in the length of the fibres during the stretch, as well as the speed that occurs.

Secondary (flower-spray) endings

These are clustered at the end segments of many fibres and only detect changes in the length of muscle fibres.

Extrafusal fibres

This is a class of muscle fibre innervated by alpha motor neurons.

- Ordinary muscle

- Contains contractile elements (myofibrils) throughout its entire length.

- Fusus means “spindle”

Stretch Reflex

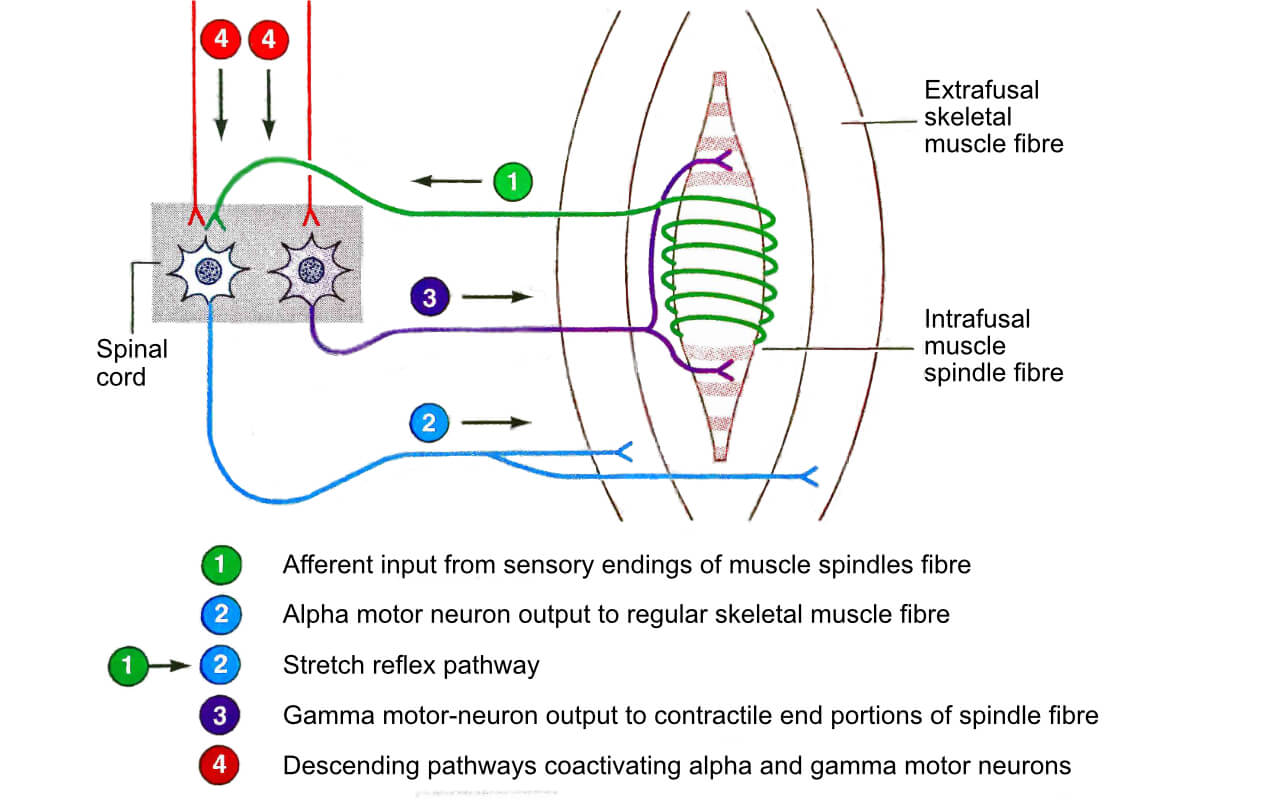

When a muscle is passively stretched (stretched without the muscle activating), its muscle spindle intrafusal fibres are also stretched.

Leads to an increase in the firing rate in the nerve fibres.

Directly connected to the motor neuron that innervates the extrafusal fibres of the same muscle.

→ Results in contraction of that muscle

A local negative-feedback mechanism resists any passive changes in muscle length so that optimal resting length can be maintained.

Helps prevent passive stretch placed upon muscles due to gravitational forces.

Example:

Extensor Muscles

→ When the knee joint buckles because of gravity

→ Quadricep muscles are stretched

→ Contraction of muscle

→ Straighten out the knee

→ Remain standing

→ Pushing yourself too far in a stretch.

→ You may notice that body part twitching/contracting (Sherwood & Kell, 2010)

Factors Affecting Range Of Motion (ROM)

There are several factors that affect ROM, however, there are always exceptions. The following are factors

that can affect how flexibility.

- Age

- ROM typically decreases in adulthood due to:

- Muscle atrophy

- Physical inactivity

- Loss of elasticity in soft tissues

- Increased fibrous connective tissue

- Studies have shown that joint flexibility can be improved across all age groups. (Nieman, 2011)

- Disease

- Arthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Osteoporosis

Types of Stretching

Static Stretching

What are Static Stretches?

- Stationary exercises that apply a stretch to a muscle group for a prolonged period of time

- They can be considered active or passive

- Active Static Stretching

- Defined as holding a stretched position without any assistance, other than the strength of the

agonist muscle - Passive Static Stretching

- It involves being in the stretched position while holding some part of the body, or with the

assistance of a partner or piece of equipment

What are the Benefits?

- It is a safer stretching techniques, especially for individuals who are sedentary or untrained. It uses

slow and controlled movements which help decrease the risk of injury

When Should I Stretch?

- Recommended to do at the end of an exercise program

Dynamic Stretching

What are Dynamic Stretches?

- It involves the gradual/controlled movement from one body position to another, with a smooth return to

the starting point. With this, you should see a gradual increase in range of motion as the movement is

repeated - Stretching movements more specific to the activity that you’re about to partake in

What are the Benefits?

- Typically dynamic stretches are more closely related to the activities that athletes partake in and are

considered more functional

When Should I Stretch?

- Typically part of a warm-up routine involving active movements going through ROM

Ballistic Stretching

What are Ballistic Stretches?

- Stretching exercises that use a fast bouncing motion to produce stretch and increase range of motion

What are the Benefits?

- Using the fast motion bouncing motion, it has the ability to produce a greater range of motion

When Should I Stretch?

- Typically part of a warm-up routine involving active movements going through ROM

- Not recommended in most cases

- Higher risk of injury, high resistance to stretch

Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF Stretching Exercises)

What are Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) Stretching Exercises?

- Studies have shown that PNF stretching improves ROM more effectively. However, for most techniques it requires an assistant. The various techniques are:

- Contract-Relax (CR)

- Contract-Relax Agonist Contract (CRAC)

Contract-Relax (CR)

- Step 1: Isometrically contract the target muscle group

- Step 2: Immediately follow with slow, passive stretching of the target muscle group.

Contract-Relax Agonist Contract (CRAC)

- Step 1: Isometrically contract the target muscle group

- Step 2: Immediately follow with slow, passive stretching of the target muscle group.

- However, you will actively contract the opposing muscle group at the same time as the stretch.

- An example of this: When stretching the pectoral muscles

- Patient extends their arms horizontally

- The patient isometrically contracts the pectoral muscles as their partner offers resistance to horizontal flexion

- Following the isometric contraction, the partner slowly stretches the pecs as the patient actively contracts the horizontal extensors in the upper back

- Stretch the muscle by going to the end of its ROM

- Isometrically contract the stretched muscle group for 5-10 seconds

- Can use a partner or an immovable object

- Isometric contraction should be 20-75% of maximum voluntary contraction

- Relax the muscle

- Apply the passive stretch to it again, this time trying to take it further into its ROM

- Hold the stretch for 10-30 seconds

- CRAC – contract the opposing muscle group slightly for 5-6 seconds

- This push-relax sequence should be repeated at least three times

- Can produce dramatic increases in range of motion during one stretching session

What are the Benefits?

- Much like static stretching exercises, PNF stretches are best to be done after exercising

When Should I Stretch?

Stretching Exercises Guideline

- It is recommended that a warm-up is done prior to stretching

- It’s still highly debated and researched, but a dynamic warm-up, specific to the activity you are going

to do is recommended - Static or PNF stretching is best for after exercising

- Stretch all muscle groups

- Stretch in a controlled manner, do not bounce

- Hold the stretch for 20-30 seconds, and do a minimum 2-3 repetitions of the stretch for each muscle group

- Stretch to your limit, but DO NOT push yourself to the point of pain

- Maintain a slow, calm, rhythmical breathing pattern while holding the stretch

- A daily stretching program is also recommended to maintain flexibility